This story was published in The Clackamas Literary Review in 2021.

BTW: There is an interesting “behind the publishing scenes” note following the story. A peek at the sausage-making.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

THE SILVER STREAKER

We were on the third lap inside the Washington Square Mall. It was only a few minutes before opening and Phil and Connie, this morning’s pace-setters for our walking group, the Silver Streakers, had gone turbo. Yeah, well, they didn’t have a knee replaced six months ago. Or lose their spouse of 37 years two months ago. And not heard back from their daughter or grandkids for three maybe four weeks now. As those show-offs pulled away, I remember trying to say:

I (pant) can’t (pant) can’t (pant) really keep up. Can’t.

I sat on the bench by the Welcome Center—breathing hard— and watched my herd of fat-asses double-time past the escalators. Howie was passing Warren on the outside of the turn. That’s just plain disrespectful.

My new knee was angry with me and really letting me know it.

I hope Roxie got the money for her Nutcracker costume in time. Last year a mouse, this year a snowflake. I’ll fly down to see it right before Christmas. First one without Elizab—

Lord Almighty! Christ, that hurts!

That’s what I get for taking a week off. But I had a cold. Nobody enjoys exerting themselves with a runny nose. Now I can smell the bakery. I hate this diet. Elizabeth would have kept me on this diet no matter what. If I have to buy more pants… What’s after XXL? Is there really another X? So embarrassing.

Two brightly illuminated young hikers beamed down on me from a mountain, their teeth whiter than the snow surrounding their ridiculously fit forms. Made in Oregon! shouted the advertising copy. Metal gates clattered open, announcing another day of retail and all the hopes and dreams that go with it. Mall security turned some keys and a few weekday shoppers trickled in.

I checked my phone. Still no response from my daughter. Maybe I came on a little strong with advice regarding Roxie’s ear infection. But, Jeez, Pam—come on—at least let me know you got the funds. And how was I supposed to plan a visit without a firm date? Sure, it wasn’t for a couple of months, but what if the airfares go up? So I checked the airlines. Then email. Then the weather. Rain possible tonight between one and five. Not even a quarter of an inch. I’ll close the windows anyway, before going to bed. God, my knee was hurting.

Peetah-doop! A message. Pam? No. Shari’s was offering that pie deal for seniors again. Maybe shoot over there before I go to—

Darn it. Phil and Connie turned the distant corner, chugging hard. I got up and headed for the restroom—always a good excuse—behind the Welcome Center. Darn it again: the custodian had blocked it off for cleaning. I abruptly changed course and headed for the nearby escalator to use the restroom up off the Food Court. What ever would we do without escalators? If I had to actually climb these stairs I’d starve.

Coming out of the men’s room, I wanted coffee but not a single food outlet had opened. I wasn’t about to stand in line at the Starbucks on the main floor. Maybe try that new drive-thru. If I ran into any of the group on my way out, I’d tell them that:

I had a doctor’s appointment.

That Shari’s was doing that pie thing.

That it was going to rain tonight.

And that my daughter had gotten back to me with the dates for my trip.

I was getting all this in order as I rode down the escalator…when I saw the strangest thing.

On the up escalator, ten yards away, was a small child, a girl as it turned out. She could only be seen by the little pink pig ears on the top of her hat, and the tiny hand that gripped the escalator’s black rubber rail. This little upright piglet seemed to be riding to the unopened Food Court without any adult accompaniment. I swung my gaze a full one-eighty, looking down to the mall floor, then up to the Food Court. No, there was absolutely no parent attending to her. The escalator was entirely empty of guardians. This child is totally lost and alone, I thought. As I reached the bottom, and hurriedly moved to the base of the up escalator, I saw the girl, in a matching pink quilted jacket, reach the top of the very long escalator—trip, almost fall—and then disappear.

This wasn’t right. I had to see about this.

Ignoring my knee, I bounded up the up escalator, which resulted in double speed and triple pain. Halfway up, already out of breath, I had to stop and just ride. Who knows? Maybe her parents had just gotten ahead of her and she was safely back in their care.

Nope. Here she comes, descending the down side to my up side. Man, this kid was on the move! Upon reaching the top, I limp-cantered—still out of breath— back down the set of stairs that divided the escalators. My knee was literally barking, howling for mercy. When I reached the main floor, she was gone.

This was not my child, but once parental instincts fire off she might as well be. What if she wanders out to the parking lot? What if she rides the escalator again and an untied shoe lace catches in the teeth, the grinding maw of those moving metal steps? What if a sick person grabs her for any number of horrific reasons?

My Elizabeth would be so proud of how I’m handling this. She would understand how this noble, selfless pursuit was inflaming my knee. And how to rub the ointment on it.

The mall, open a mere ten minutes, was very quiet, with only a few shoppers in the distance. Another clump of mall-walkers was thundering through. This was a rival walking gang— The Beaverton Breeze—that annoyed the heck out of us because it traveled counterclockwise. Clockwise is the rule. Maybe the unspoken rule, but still the rule. Which is why we suspended our good manners to sneeringly refer to them as The Pudgy Plodders.

As these determined plush-soled souls waddled by, I asked a pleasant couple, straggling to catch the clump, if they had seen my girl. No? Okay, that meant This Little Piggy had gone to Market: to the left. I began an urgent trot down the big hall. I was not only out of breath, my knee throbbing, but beginning to pale with fear. That awful dry cotton-mouth was happening and my stomach was painfully filling with acid. Which meant no Key Lime at Shari’s. Alternate generous slices of Coconut Cream and Boston Cream oughta do it.

Hey. Focus.

Half-jogging, half-limping, I began frantically zig-zagging between mid-aisle pop-up kiosks. I stopped at every store on both sides of the big hall, bursting into:

Anthropologie: Have you seen…?

Game Stop: Did a little…?

Sunglass Hut: All by herself!

The Duck Store: Pig…she’s a pig!

The Starwars Store: No bigger than Yoda!

At the end of the hall, I looked left then right. There she was. The tiniest thing, toddling towards Target. Must be seventy yards down the corridor. Still entirely alone. She must have, at this point, wandered a good half mile through this enormous shopping center, a three or four year old child, all on her own. Not one adult has attempted to save her from the Escalator Mangle-Monster, the Wheels of Death Crusher-Bus, the Claws of the Kid-Grabber-Nappers Gang. Not one other person.

Only I.

I alone have flung my tri-focal eyeglasses to the floor. I alone have ripped open my L.L. Bean shirt to reveal…the Big Red Double S.

I fly down the hall, 30 feet in the air, muscular arms extended, shops and vending kiosks whizzing by. In the distance I see the huge glass door of a store swung open by two chattering teens as they exit. The tiny girl enters, completely unseen. Within three seconds I touch down—the red-booted foot of my good leg artistically extended, my silvery cape fluttering above—at the store:

Apple.

I am halted by a phalanx of blue shirted nerd-geeks, swarming me like Lex Luther’s minions, demanding my appointment time, my model number, my operating system. Beyond them, halfway into the store, I see my pig-child walk up to a young woman who is intently hunched over a new cell phone. The child tugs on her mom’s sleeve. The mother looks down, smiles at her baby, softly strokes those soft pig ears. Goes back to her cell.

Geniuses.

I squeeze my eyes shut, initiate Omni-Vision. I see a shadowy figure by the fountain, behind a potted palm, his greedy eyes locked on the little girl. I see the pig hat lying outside on the pavement, printed darkly with tire treads. At the top of the escalator I see fresh bright blood flowing from the grinning steel jaws.

Upon opening my eyes, I realize: this girl, my girl, does not belong to this woman anymore. I cannot allow it. With my Super-Chill breath I freeze everyone in the store. I pick up the child, cradle her in my arms and fly down the hall, my cape snapping in the wind as I slalom kiosks. Out the front entrance and up, up and away: to my Fortress of Silver Streaker Solitude!

Where my beloved Elizabeth is waiting with open arms to care for yet another rescued child.

Ten years from now, this one will debut triumphantly as:

Pig Girl! Protector of Lost Mall Children.

I will have taught her to fly, to disable escalators with the laser-magnetos in her robotic corkscrew tail, to stop a speeding bus with a single trotter and to render bad guys senseless with her Super-Squeal.

Yes. This. All this.

After a quick stop at Shari’s.

#

***************************

Hope you enjoyed that. The Clackamas Literary Review badly botched the printing of this story. For some reason, random hyphens appeared throughout. I had a very civil exchange of emails with the editor. His excuse was that the students who were in charge of the magazine “were very busy”. Though he was properly apologetic, inside I was absolutely furious. The only way to let off all that steam was to write the following. Here’s the UNSENT letter that burst out of my fuming blow-hole.

**************************************************

One of the oxymoronic aspects of submitting short stories to literary magazines is the so-called Positive Rejection. Make no mistake: it’s still a rejection. But there is a note attached, such as, “Sorry that we’re unable to use this story in our upcoming issue, but we admired it and hope you will continue to send us your work.” Meaning: Your story came in fourteenth. Well, the following piece, always a bridesmaid, never the bride, has received no fewer than six PR’s.

Not its time, I guess.

~*~

LAZY DAYS

Joseph and Janet reserved their favorite site, Number 58, in Sunset Bay State Park as soon as online reservations became available. October was always less crowded and the nights not too cold on this part of Oregon’s coast. Their RV was a 27 foot Lazy Days motorhome, a perfect fit for them and their small mixed-breed terrier, Stanley. This black and white dog had a short smooth coat and a spotted pot-belly like a miniature pig.

The campsite was near the end of the line of rentals along Loop A. To their left they would have the same neighbor for the month, while to the right they would enjoy a different neighbor every few days. That variety had worked well for them in the past. There was a trailhead nearby that forked left to a cove with a crescent-shaped beach. To the right, the path led to a spectacular set of cliffs overlooking the thundering Pacific.

During the month, to the right, their neighbors would be:

The Bergs. A 44 foot Class A Monaco Emperor.

Jenna and Lynette. A 24 foot Airstream.

Graham. An Arctic Fox 25 foot trailer.

And finally, their daughter, Tally and her new partner Gabe, who was bringing his nine year-old son, Emmet. In Gabe’s parents’ old Bounder. 34 foot.

To the left, their full-time neighbor would be a young woman in a tiny 10 foot Scamp.

Joseph had recently been diagnosed with prostate cancer. He went in for his annual and came out without his famous sense of humor. Radiation would begin upon their return to the city. Their retirement plans, which had included a European trip, were put on hold.

Janet reacted by binge-watching back-to-back streaming series. Joseph would lay awake alone with his thoughts while Henry VIII went through wives in the living room. Desperately seeking unconsciousness, Joseph tried an old trick, tuning the clock-radio to the hissing between stations. Nonetheless, ghoulish shrieking and ancient cannon would pierce the white-noise barrier, tormenting his sleep. As dawn approached the sun charged the ionosphere and the station frequencies moved. This meant radio chatter intruding into his dreams, already weighted with bombastic declarations of sovereignty.

Stanley, who was up if anyone was up, no longer slept between Joseph’s feet.

These mornings, as Joseph woke in a dense fog and stumbled into the bathroom, Janet and the dog would be crawling into bed, both exhausted by her viewing marathon. It had been a strange, rough couple of weeks. They were counting on this camping trip, away from the internet, to bring them back to themselves.

They maneuvered into their site with practiced ease. These old state parks were laid out for comfort and privacy with generous spaces, picnic tables built to last a millennium and tall laurel hedges between spaces. Joseph and Janet shared a secret love of laurel. In Greek Drama 101, he had worn a laurel wreath as Creon in “Oedipus Rex.” Janet had played Jocasta. They first kissed in the wings, right after she had hung herself. After their first sex, in his dorm room, Janet had reached up, brought the laurel wreath down from the bedpost and placed it on his head, crowning him “Joseph, Victorious in Love.” From that day on, he was Joseph, not Joe.

On the first day, they were without benefit of neighbors. That evening they took their first walk to the cliff, holding hands. Stanley hopped and bit after a tiny, evasive blue moth and they laughed for the first time in weeks. The waves slammed against the rocky shore. To Janet, the chaos of it was overpowering in a way it hadn’t been before. She looked to Joseph. He was lost in the inward mid-distance stare he had adopted as of late.

When they returned, as if it had waited until it could slip in unnoticed, the Scamp was sitting in the site to their left. Shaped like a pharmaceutical capsule, its ivory fiberglass glowed in the dusk. They would not lay eyes on the occupant for two days.

The next morning brought the Bergs in their titanic RV. Thick steel columns descended from the undercarriage to attain proper leveling. A vast azure awning hummed into position.

A side-compartment hatch door hissed to reveal an entire open-air kitchen, barbecue/smoker attached. On the roof, a satellite dish and wifi booster antenna whirred, rising to the proper azimuth and elevation.

Joseph raised both eyebrows. “What, no surface-to-air missiles?’

“Like landing on Mars,” whispered Janet.

Next, the Slide-out Extravaganza. Hydraulics and screw-drives thrummed and whined as the walls extended, nearly doubling the Emperor’s kingdom. One slide-out, almost the size of Joseph and Janet’s entire RV, hung over most of the picnic table, rendering it useless.

Joseph turned to Janet. “Not exactly ‘camping,’ is it?”

“I know. But what exactly is it?” said Janet. “Oh, no. Here he comes. That’s quite a chapeau.” She retreated into their RV. “He’s all yours, pardner.”

Their new neighbor strolled on over with a jovial “Howdy, amigo!” A short, stocky fellow in a fluorescent plaid shirt and a high, double-peaked Stetson, he dove right in.

“The Emperor retails north of half a mil. Talked the guy down to 379 cash. Never knew what hit him. But then again, sir, that’s what I do, sir.”

A bone-crusher handshake.

“Hal Berg, Berg Dealerships, Collin County, Texas.”

Damn, thought Joseph, that hat makes him bigger’n all outdoors.

“Milly’s on KP. C’mon over for breakfast. Bring your wife. Oops! I mean partner. Hell, yeah! We been in Or-a-gone before.”

And up into the palatial bus he ascended, hollering, “Milly-gal! We got company!”

“Oh, no you don’t,” said Joseph under his breath, vowing to lay low for days.

The following evening on the cliff trail, Stanley, sniffing aggressively, yanked Joseph off-path toward a grove of junipers. Between the trunks, Joseph could see a naked bearded man doing push-ups. Then a pair of white arms reached up and encircled his neck.

Joseph pulled Stanley back to the path saying, “Well, Stanley, those weren’t push-ups. But that was a man.”

At the top of the trail, he lifted the dog to look over the fence a few feet back from the edge of the cliff. Stanley went delirious with the dozen scents the wind pushed into his black, wet nose. Out where the sky met the sea, a scalpel of clouds sliced the orange-pink setting sun in half.

Joseph closed his eyes. The white arms wreathed his neck. He opened his eyes to see that half the sun had been cut away. This day was done. How many more?

Hal Berg spent the week inviting red-blooded football fans throughout the loops to his “Tailgate Touchdown Tornado!” on Sunday afternoon. Janet, not a fan of football—or Hal—stayed in. Joseph, fascinated by the spectacle, wandered over, “for anthropological research purposes.”

A couple of dozen fans, carrying chairs, arrived with pot-luck containers.

Gad, these people are exceedingly girth-some.

One exceptionally heavy man, due to his prodigious belly over-hang, could not reach the buffet table. His wife brought him plate after plate, piled high with roast beast. Stanley viewed him and his meat as a group.

After the first inhalation of “vittles with all the fixin’s”, Hal gathered the pork and pigskin addicts around the rear quarter panel of his RV. He waved a remote, pressed a button and out of the Emperor’s ass emerged a 66-inch TV. He basked in the oohs and ahhs.

Joseph turned to no one in particular and said, “I love being out in nature, don’t you?”

“Now, lessee how my ’Boys ’r doin’!” Hal barked. To which Stanley and five other dogs yapped their approval. Up came the Dallas game. “Let’s take a gander at y’all’s teams!” The screen split, then subdivided until there were eight games showing. The multitude gasped, no less than had it been the loaves and fishes. Hal polled the fans, and eight became four. Once word got around that there was wifi, everyone sank into their cellphones. Soon no one was talking to each other. Joseph was appalled.

Suddenly a chair collapsed under the weight of the morbidly obese guest. Joseph felt the ground shake.

Hal exclaimed, “Whoa! When these offensive linemen go down, you really know it!”

The embarrassed fat man struggled to get up, then stumbled heavily onto his knees. He remained on all fours, head hung low, breathing hard. His wife approached and knelt on one knee before him. He placed a hand on her shoulder. She braced her hands on her thigh and leaned forward to support him. He climbed to his feet and put his hand out in turn to help his wife up. She stood and whispered in his ear. They smiled at each other.

He glared at the crowd and declared, “I was a lineman. Right tackle. Started every game, senior year. Tough league, too.”

All nodded and ducked back into their cells. He popped a beer can as if snapping the neck of a small mammal. On one screen, an illegal helmet-spearing took place. The mob erupted. Under this cover, the former high school lineman limped off to a tree, leaned against it, winced and rubbed his knee. Joseph withdrew, unseen. Poor guy. Cannot sit. Cannot stand.

“Had enough?” Janet asked from her camping chair. “Uh-huh,” said Joseph.

Stanley, a mouth full of leash, pogo-ed stickless from knee to belt.

They headed towards the cove, away from the din of competing color commentaries. As they strolled through a grove of Douglas firs, Janet asked, “How was the game?”

“Which one? He had four of them up on that screen.”

“What? That’s very ADHD.”

“Tell me. And they were all on their phones. This big fellow broke a chair. Hurt himself but afraid to show it. Why are we like that?”

Then, to himself: “Tough being tough.”

They fell silent. Bright orange-yellow leaves scuddered across their path. Off to one side, in a in a clearing among large oaks and maples was a little wooden outdoor theater with a slanted overhanging roof. Warmed by the memory of their time together onstage, Janet reached for Joseph’s hand. He chose that moment to adjust his cap. She returned her hand to its pocket, to her own warmth. Soon they rounded the base of a rocky precipice to behold the perfectly circular little bay. The sun hung above the horizon by precisely its own diameter. They followed Stanley to where the arc of sandy shore began. In the near distance, halfway to the water, they saw a couple necking passionately on the beach.

“Hey. Isn’t that…”

“Yes, it is. Lady Scamp and her boyfriend.”

“I thought he had a beard.”

“Maybe he shaved.”

“No, you said he had dark brown hair. This guy is blonde. With a man-bun.”

“Is that what they call it? I thought it was a Samurai top-knot.”

Scamp-girl was now on top. The man-bun man had his hands up inside her loose sweater.

She bent to kiss him, rose like a bough in the wind, then bent down again.

“Ellen’s son calls his a man-bun.”

“Why not just call it a bun?”

They observed the lovers for a moment.

“Do you think that avocado is ready?”

“Should be.”

Stanley, salt-air starving, strained on the leash, pulling them home. As they passed the Scamp they saw, parked next to it, a Subaru with yellow kayaks on the roof.

Joseph broke the long silence. “Does it cost extra to get a Subaru without kayaks?”

“I don’t think that’s an option.”

“You mean if you have them removed it voids the warranty?”

“Probably. You know: Love. It’s what makes a Subaru a—”

“The love is in the kayaks?”

“When you’re young.”

“Where do they put it when you’re old?”

“In the margarita in the cup holder.”

Cheers burst from inside the Emperor. The remaining few, true fanatics, were watching the four games on a “tiny” 49-inch TV.

“Sure you don’t want to join them? Sounds like fun. You could bring some guacamole over,” said Janet.

Joseph looked at her as if she had lost her mind.

“You know I can’t watch four games on anything less than a 66-inch screen.”

He fake-scowled at her smile. “Where’s my book?”

The following morning Hal was noisily up-cranking, de-leveling and retracting his numerous slide-outs. “Looks like the HMS Emperor is preparing to push away from the dock,” Janet observed. A sudden horrific grinding elicited a cascade of foul language from the ship’s captain. Joseph hoped it wasn’t what he thought it was.

It was. The enormous picnic table-devouring slide-out was stuck in the out position. Hal exploded when Roadside Assistance Premium Platinum informed him over his cellphone that slide-out mechanisms were not covered. He bull-bellowed at the dealer in Texas. Then, near-weepy, pleaded with a local RV mechanic who could not get to the park until Tuesday.

While Hal was fuming and stomping around, Jenna and Lynette pulled up, towing their tidy, shiny vintage Airstream.

They asked—not unkindly—if Hal was aware checkout time was an hour ago. They would like to move into “their” campsite. Hal, barely keeping the lid on, said “his” site would be available sometime tomorrow, depending on the mechanic.

“ETD unknown. Can’t evac ’til then, ladies.” He waved them away. “You gotcherselves plenty nice little spots on Loop D.”

Lynette leapt out of the pickup and was nose to nose with Hal within seconds. Jenna—also a pistol—brought a park ranger to the party. She explained that her dogs liked to be by the beach, that she was not going to walk them through three loops of unleashed, unvaccinated dogs, and that once her babies were upset, they would not venture outside, which was the whole point of reserving this campsite. Her children—she actually used that word—had special needs for which she and Lynette had carefully arranged.

As things began to boil over, a stout gal in baggy waders—grasping a clam rake and bucket—ambled around the corner, stood on the road and watched the uproar. Hal’s phone sang The Yellow Rose of Texas. He took the call. The ranger seized the opportunity to reason with Jenna. In the resulting relative calm, the clam-lady remarked loudly: “So then, what? The manual release don’t work?”

In the stunned silence Stanley stretched and yawned.

Within two minutes, four people were able to heave-ho the slide-out inward about two feet, leaving a couple of feet hanging out but in enough for a thoroughly humiliated Hal to back out and set sail for the far flung backwaters of Loop D.

Out of the Airstream poured three identical Shelties, groomed to perfection, a soft blur of yippee-hops.

Joseph looked down at Stanley and said, “Looks like your turn in the barrel this week, my man.” Stanley’s ears were pinned back as his pink tongue nervously licked his black lips. His tail curled down and around his very public private parts.

“Thanks for this, buddy. I needed a break.”

That evening Joseph and Janet, led by Stanley, came upon Jenna and Lynette on the cliff trail. Actually, they came upon an argument heard from around a bend in the sea-grassed dunes.

“Then why bother to come with us?”

“I need space sometimes, okay?!”

“We’ll give you all the space you want. But not during a walk!”

“I don’t know why you’re making such a big fuss about—”

“Fuck’s sake, Lynette! You know it triggers Timmy’s anxiety. He falls apart if we split up during a walk.”

“No he doesn’t.”

“He does! You know he does! I have absolutely had it with you!!”

Joseph and Janet, still unseen, glanced at each other, turned around and went back down the path. Stanley scented the neurosis and began trembling. Janet picked him up.

“You wouldn’t leave Stanley and I and just go out on your own path, would you?”

“Count on it,” said Joseph. “Several times. Tomorrow.”

“Thank god. Stanley’s sick of you.”

“I’m sick of him. Well, not all of him. Just part of him.”

“I know. His breath.”

“His breath.”

Joseph woke to laughter. Janet was serving coffee—his coffee, by the way— to Jenna and Lynette as they sat at the picnic table. Turns out they had all been grade school teachers at some point. A Sheltie posed regally in each lap, receiving a luxurious brushing.

So that’s what her life will be like. She really doesn’t need me anymore.

He dressed and shoved Stanley inside his jacket. He made it by the picnic table, refusing to join them, cap down to his nose, with the barest minimum of niceties. Bordering on rudeness, really.

That’s what I’m going to do now, he thought. I’m gonna build me a cabin on the border of rudeness. Live there from now on.

At the cove, he saw Scamp-woman and her man out beyond the surf in the yellow kayaks. Their bright red paddles semaphored to each other.

Signals of affection, no doubt. He then heard a low feral sound from Stanley, who had uncovered something and was writhing madly upon it. It was a large dead seagull. As Joseph knelt to disengage the living beast from the dead one, he saw into the depths of the bird’s entrails. He remembered from his Greek drama that the oracle Tiresias would scrutinize the innards of birds to read the signs and divine the future.

Read the future? He contemplated the splayed corpse before him. This is the future.

There was excited shouting from the kayaks. He stood up to see a whale’s plume misting the air, not 50 yards from the paddlers. For the next five minutes the leviathan circled them, sounded three times, then was gone. A family stood on the beach and cheered. The bun-man pumped his paddle and woo-hooed.

Joseph wondered if he could tie a kayak onto the roof of the RV.

Maybe. But not two.

Janet opened the door for them.

“How was your—Good Christ!” She held her hand like a gas mask over her face.

“What?”

“What is that smell?! What did he get into?!”

“Oh, I guess it’s the seagull.”

“What seagull? A dead seagull?!”

“Oh, gosh that is bad.”

“Out! Get him out! Lord, I think I’m going to retch. Out!”

As the show-quality Shelties paraded by—noses raised in distain—Stanley sat in a tub of white vinegar with cold, matted fur, looking after them with envy as they headed in the direction of that carrion buffet.

As Joseph lathered the dog’s underbelly, his thoughts wandered.

A hundred pellets, the doctor said. Injected by needle up through the—what do the kids call it?—the taint. Emitting radiation. Barium, I think he said. So small they are just left behind— like beer cans after a frat party—in and around the prostate. Still and all, no matter how small, a hundred seems like a lot.

Stanley bit into the enemy sponge and ran with it. Joseph let him run.

If Tiresias the Oracle pulled in next to us, towing an ancient canned ham of a trailer, would I have the guts—so to speak—to ask him to read a bird for me? Would I really want to know?

After three washings, Stanley smelled like lavender, vinegar and rotten seagull. He was banished to the outside tie-up for the day. Joining Stanley in exile, Joseph sat reading next to the hedge. A cool morning breeze rattled the laurel leaves. The Subaru pulled in next-door, kayaks glistening. Shortly after, marijuana smoke wafted through the hedge, followed by the unmistakable sounds of lovemaking. Stanley lay down and sighed.

“What? You miss that?” asked Joseph. “We all do.”

The side effects are a bitch. Why did I visit all those medical websites?

He watched Stanley chew on the rope.

Was Tiresias a man or a woman? Wasn’t he both? Or neither? I think I might believe someone who had been both. Or neither.

Fifteen minutes later the Scamp-screwing neared another hard-earned round of orgasms.

Janet slowly opened the door in mock horror, eyes comically bulging. A withering moan of desire from the Scamp sent her tiptoeing—hand over mouth to contain the giggles—to where Joseph sat. She bent down, whispered, “And it’s not even ten o’clock!”

He caught her wrist to pull her down onto his lap and threw his arms around her, then went romantically deadpan and whispered into her ear, “Love. It’s what makes a Subaru a-”

Janet again clapped a hand over her mouth and began heaving. She abruptly stopped as an enormous, low hissing groan emanated from the Scamp, an almost inhuman sound, like something issuing out of a blowhole.

“How the hell did they get a whale inside that thing?” Joseph thought aloud.

Janet began frantically kicking both legs to keep from imploding. A flip-flop flew through the air. Stanley snagged it on the fly. The Scamp’s tiny springs began rhythmic squeaking in perfect counterpoint to male grunting.

The absurd contrast of squeak to grunt now had Joseph biting his lips.

Janet, tears streaming down her face whispered, “Now there’s a dolphin?!”

“And it’s calling the whale daddy.”

Janet erupted, blowing snot into her hand.

Stanley jumped onto her, began lapping the hand and then her face. Janet slid off Joseph’s lap onto the grass, convulsing. Stanley slid with her to continue licking her tears. She laid there gasping, looking up at the treetops. She hadn’t felt this good since forever. Joseph smiled down at her. Neither had he.

“Mind if I join you and your friend on this beautiful day the Lord has given us?”

At first, Joseph didn’t mind walking with Graham, their next neighbor. He was a newly retired, recently widowed minister.

It was, in fact, instructive to hear how someone recalls a deceased spouse. The fond memories, the funny stories. The moist, quivering tone as the beloved floated in the air before the survivor’s adoring gaze. It was when Graham began to repeat anecdotes already shared barely a half hour earlier that Joseph realized the old preacher was on a short loop of auto-play/shuffle mode. On their fourth and last walk—of course, the new friend didn’t know yet it would be the last—Graham re-revisited his wife’s meatloaf. Joseph imagined Janet without him.

How much better she would be. How lost she would be. How much I hope she would fill the hole my passing would leave. How impossible that would be. Maybe she would hang herself, then come find me in the wings and we’d kiss behind the set as Oedipus suffers onstage for our sins.

“—and that’s how the meatloaf ended up in the Sunday sermon!” Graham finished once more with a chuckle, as they returned to their campsites. They each headed into their rigs, but Graham stopped, turned away from his door and said, “Think I’ll go bask some more in God’s glory!” and headed up the cliff trail. He and Joseph had just walked three miles.

As he entered the RV, Janet was peering out the kitchen window. Scamperella was peeing in a bush.

“Yeah, well, a trailer that small’s gotta have a really tiny waste tank,” said Joseph.

“There’s a restroom right over there. What, is she going to poop in the bush, too?”

Joseph, who had begun wearing two pairs of underpants due to dribbling, said, “Aw, leave her alone.”

Janet half-rolled her eyes and changed the subject. “How’s Graham doing?” “His feet keep a-movin’ and his tongue keeps a-groovin’. So he’s okay. But I’m done.”

Janet sat across the dinette, sipping from a cup of tea. She looked directly at Joseph and said, “Tally and Gabe will be here day after tomorrow.”

After a pause, Janet continued. “Are you going to tell her?”

“I don’t want to spoil their vacation.”

“What about mine?” She stared at him hard, searching for cracks.

Joseph picked up Stanley’s favorite toy, a stuffed fox, and threw it the length of the interior. Stanley, following Janet’s lead, ignored it and stared coldly at him, too.

“Hey, that lady is hardly wearing any clothes,” were Emmet’s first words as he bounded out of the Bounder. Scamp Gal was practicing virtually naked yoga with a lithe 60-looking man in a thong. The adults regarded each other and smiled awkwardly. Except for Gabe, who smiled approvingly.

“Hi, Dad! How’s the month been so far?” said Tally, with a big hug. She had been named after Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio, Taliesin. Joseph and Janet were very artistic at that time.

“Oh, fine. I mean, you know: amusing, then annoying. Hot, then cold,” and with a gaze Scampward, “but never a dull moment to the east.”

“That’s not even a bathing suit,” whispered Emmet, peeking through the bush.

“That’s okay, Emmet, they’re doing the Sun Salute,” said Gabe. He was a dancer and choreographer. “Like I taught you, remember?”

With an overly earnest, showy inhalation, Gabe began a fully committed Sun Salute. Emmet joined him. The others watched respectfully.

Stanley, who was meeting Emmet for the first time, trampolined beside him, nose-punching his hip throughout the salute. At the end he submissively lowered his head to the ground.

“He’s doing Downward Dog!” cried Emmet.

“Oh, sure, Stanley knows yoga,” said Joseph. “Especially Push the Poop.”

Emmet laughed at the adult taking a fling at a dog doo-doo joke.

“Why is he named Stanley?”

“It’s for Lord Stanley. A great explorer. Like this little guy.”

“Lord? Like Buddha?”

“Yes. Look at this belly.”

Joseph rolled Stanley over to receive belly-rubs from them. Gabe knelt and joined in the soft pleasuring. Stanley’s eyes half-closed with rapture. Inside his open mouth, teeth glowed like snowy ranges of miniature Himalayas.

“There he goes,” said Joseph, “into a bliss only Buddha himself could dream of.”

Gabe smiled knowingly. “Ah, but the Buddha would say that Stanley’s bliss is an illusion, as is our suffering. It’s all a dream.”

“I don’t know about that,” countered Joseph, rather firmly. “Stanley’s bliss certainly seems real to Stanley. Shall we ask him?”

Emmet worriedly looked from Joseph to Gabe.

Fuck me. They’ve been here three minutes and I’m already in an eschatological pissing contest for the mind of this child. What is the matter with me?

Janet and Tally shot warning looks at Joseph and Gabe. They quickly retreated into the safety of dog play and RV talk. Before they knew it, they were all making sandwiches for lunch.

As they ate, Scamp-Goddess sauntered by, hand-in-hand with the older gentleman, both in flowing robes.

“Is that her father?” asked Emmet.

“No, that’s her boyfriend,” said Gabe.

“Isn’t he awful old to be—”

“No, not at all. Some women enjoy the company of an older, wiser man.”

“So he’s a wise man? I don’t think wise men have girlfriends.”

“Why not?” asked Tally.

“I dunno. It looks weird.”

Thank god for this kid, thought Joseph.

Before dinner, Tally and Joseph strolled to the cove.

“You seem kind of stressed, Dad. Everything okay?”

He looked out to where the whale had circled the kayak lovers.

“No, honey.” He told her everything.

Back at the campsite, sitting around the fire-ring, Joseph and Gabe bloviated upon The Artistic Imperative in The Digital Age.

Sobbing could be heard from inside the Bounder.

They sat at the picnic table to kale salad and vegan hotdogs. Stanley, with nothing to lust for, sat with rare good behavior on Tally’s lap, licking an occasional tear.

Janet suggested a sunset walk along the cliff trail. Emmet suddenly stood erect and declaimed in a loud stage voice, all in one breath: “Yes I wish most earnestly to see if Helios mastering his fiery steeds as they pull the chariot upon which the sun rides across the sky is able yet once again to return said golden orb to Apollo’s palace wherein the sun resides throughout the obsidian night.”

He sat to applause. Gabe beamed proudly. Tally and Janet smiled at each other with ecstatic love. Emmet squirmed with the triumphant embarrassment of the victorious child performer. Joseph took in each and every face, the plain, pure emotion that poured forth from all. But there was none from him.

For I now have become a watcher. A gatherer of signs. A keeper of moments. Mine own Tiresias.

That evening they all walked up to the cliff. A windstorm had blown an opening in the fence. They paused to admire the blazing sunset, then moved on. Trailing behind the others, Joseph slipped between the fence posts and stepped out to the edge of the precipice. The booming of the waves seemed to come from the center of the earth. Bitterly cold salt-wind whipped his face. Seagulls wheeled and screamed below. On the horizon Helios strained at the reigns, landing his snorting beasts in the kingdom of darkness. The ocean went on forever.

It does seem like a dream, doesn’t it?

He turned to see his family walking away from him, down the path on the other side of the fence, sheltered from the wind.

Emmet was holding out a stick.

Stanley was jumping with joy.

#

==========================================================

A few years after I wrote this, three close friends, in the space of about three months, were diagnosed with prostate cancer. Needless to say, revisiting this piece has more meaning for me now.

———————————-*******************************———————————-

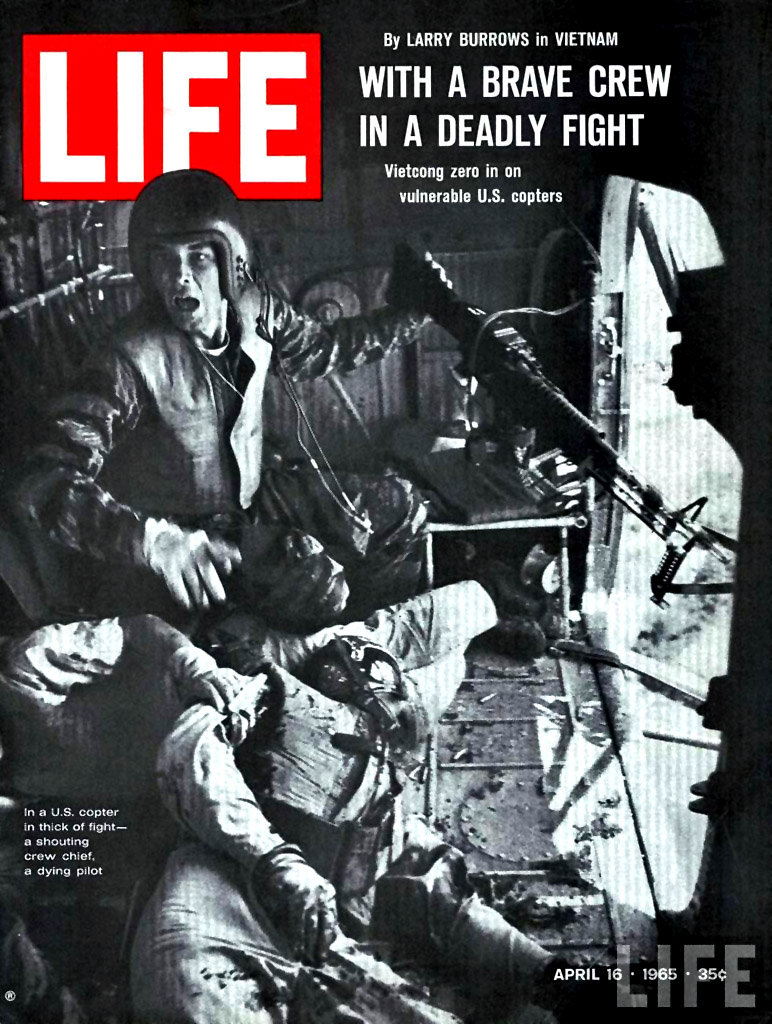

This is an early attempt at a kind of philosophical horror story. I think it would make a good Black Mirror episode. Or to my generation, The Twilight Zone. I’m including a photo of the Life Magazine cover that is essential to the plot.

AFTER ALL

The silence breaks over me in waves.

At midnight—a few hours ago—the day arrived. At last.

Fifty years.

I did not go to bed but instead sat at my desk. Because I’m not sure when, or how it will happen, how it will proceed. This sort of thing doesn’t come with a manual. There’s no app or website to log into. For all I knew, at the stroke—or nowadays, pixel shift—of midnight, it would present itself.

11:59 to 12:00 Only the first 1 and the : remain the same. But nothing has changed since then. Except for the silence. I mean total silence. When I first noticed it, around 2:00 a.m., I tested it by dropping my pen on the desktop. Not a sound. I lifted the outer little silver sphere of the desktop Newton’s cradle and let it swing, listening for that satisfying series of clacks. Nothing. I began reading out loud the letter to my children. Mute. At 4:30 a.m. ancient plumbing should have groaned one floor above, two apartments over, as Bill rose to fire up the furnace at the nearby elementary school. But this morning: nothing but nothing. I tried to fool myself that this was it–the silence. This would be the price. But I knew it wasn’t. It was fair warning. A clear indication that the great bargain was done. Now I sit and wait.

There is suddenly a gentle heat radiating from my sports jacket pocket. Makes sense. This happened when it was handed to me, warm and glowing, a lifetime ago. I reach into my pocket, feeling for the sacred object. Burnishing the golden profile with my thumb, picking at the tiny epaulet with my fingernail, I am almost overcome with sorrow at the wheeled orbit of human madness and folly.

Looking up, I deceive myself with the glow outside the window, a false dawn from the argon beams of the train station. I read the letter for the seventh time. It doesn’t come close to all I wish to say. I sigh—still not a sound—with resignation. My children are grown and will find their way.

Endless night. Dawn seems to be on hold as if the sun had abandoned us, weary of lighting and heating this ungrateful planet.

Then: the whistle of a train, the high call of a jay. This peeling duo, their imperfect fifth joined and supported by the bass-line rumble of the express, the rattle of windows. Followed by a massive silence, a dead calm so deep it begs to question existence itself.

Instinctively, I gaze at the bell above the door, its faded deco housing with the two silvered, air-streamed soundholes on either side, a little mid-air locomotive all its own.

The first bell tones are like a one-two combination to the gut, a bing-bong jab-cross.

Strange how the stomach hears certain startling sounds faster than the ears do, leaving a slight briny nausea on the outgoing tide.

Involuntarily pushing back from the desk, I quickly stride to the door, my haste to prevent more bing-bongs from being flung at my shocked nerves than to actually see who was flinging them.

By custom I would look through the peephole, but in this instance, as the bell–a scant foot overhead–once more buzzes, bings and bongs, I rapidly throw the lock and swing the door inward. The startled figure before me, her finger still on the buzzer, leaps a full cat’s length up and away, landing into a first position plié, then slightly bouncing as if on springs, wavers in padded silence.

In the dingy orange-blue light of the hall, my eyes take a moment to register her faded beauty. The silver hair gathered under the cranberry-blood beret. Fine, almost aristocratic features–especially the perfect nose and strong cheekbones. The proud Old Connecticut Yankee jaw topping a worn lavender scarf that Isadoras down to her knees. I did not recognize her. It had been too long.

“Why, Randall, you don’t remember me?”

With a theatrical flourish, all rounded, smooth gestures, she removes her beret, shakes her hair loose in a lustrous sterling-pearl waterfall and steps two feet back—for she knew exactly where the best light was at all times—and raises that prominent chin. Green eyes flash at me from 50 years ago.

It was like falling into the tunnel of one of those wickedly sickening water tube rides that reduces one’s humanity to a turd being flushed downward into oblivion.

She steps forward slowly, measuredly, until she could hit me with her heated breath.

“Yes. It’s me.” One more breath. “Where is it?”

Light blazes from the onrushing end of the tube. I hurtle out into nothingness, my flailing flaccid old man body crashing into the water which was, on impact, like a slab of concrete, the foundation of a house never built.

Reeling in the doorway, I close my eyes as my knees buckle. But I do not fall.

No. We are going to play this out. After all.

Leaning against the doorjamb, I open my eyes. It had been only a moment, but she was gone. From the hallway.

I turned to see her sitting on the ratty beige sofa, her red and green paisley waistcoat, hat and that endless scarf all folded next to her. She was wearing an Icelandic sweater of various blacks and grays, a pack of identical howling wolves parading across her shoulders, a short—for her age—gray wool A-line skirt, thick black leggings and mid-calf, soft jet-black leather boots with intricate chain work and odd metal ornamentation.

Uneasily I eased myself into the well-worn easy chair, feeling ill at ease. She was having none of this nonsense, and with all the ease and comfort of a truly close dear friend said, in her husky Golden Age of Hollywood movie star voice, “It’s so good to see you. After all this time.”

After. All.

She leaned forward and, from the top of the antique trunk that served as a coffee table, picked up an unlit yellowish candle—short, fat, rimmed with frozen drippings—and sniffed it.

“Mmm,” she purred, clutching it with sharply pointed dark purple nails. “Jasmine.”

Touching a fingertip to the curled, blackened wick, she quickly produced a flame that grew as the golden wax began to feed it. She inhaled the aroma with pleasure, green eyes slitting like a cat’s. Returning the candle to its place, she sat back, crossed her dancer’s legs, the metal on the boots catching the candlelight. Spreading her arms upon the back of the sofa, a raptor in final open-clawed triumph, she gazed at me with a strange admixture of curiosity and predation.

After a brief moment—predation yielding to curiosity—she again asked, “Where is it?”

“Can’t say.”

“Won’t or can’t?”

“Won’t say whether I can’t or won’t.” Oh, the false courage of the clever, quivering prey.

“No matter, of course.”

“Then why ask?”

“One out of ten hands it over. Easier for me. I’m not the chorus girl I once was.”

I heard an odd sound coming from the floor. Like water dripping, plishing upon itself. I tilted a bit to the side and beheld a small puddle on her side of the trunk table, under her foot. Then I noticed water dripping off the heel of her raised boot, the one on the end of the leg that was crossed.

My surprise—for it was not raining, had not rained—caused me to hesitantly look up to her for explanation.

“Condensation.”

Without taking her eyes off mine, which hinted of seduction, she slowly lowered her arms, softly resting her hands, one upon the other, in her lap. The three wolves on her chest seemed to silently howl at her glowing, somehow moonlit face. Locking her gaze into mine, she placed both feet on the floor, reached down to the boots, pulled a bronzed chain on each, threw a couple of silver levers or switches of some sort and, with astonishingly little effort, lifted her legs up and out of the boots.

She had no feet.

Her legs terminated perfectly, smoothly, symmetrically, narrowing just above the ankles at their thinnest. The heavy black leggings tightly silhouetted the tapered ends. She gave each its needed attention, crossing one leg then the other, finally rested them on the table, both pointed dead on me like the twin barrels of a twelve-gauge. Heat pulsed across the table top, over the scattered vintage Life magazines. A cover page, the one with me on it, began to curl. My left knee, closest to her, roasted.

So this was it. Resign. Struggle. Accept. Fight.

The twin terrors of give up/let’s roll swung against each other. Those silver balls on a string, the outer balls clacking, swinging up, but the middle ball staying pat, firm, the energy passing through, but not moving it. I was three spheres in now, one away from center. Attaining that, I would reach into my pocket and give her what she wanted.

She rose from the couch. No, not as in standing. She rose from the couch, floated, then assumed an upright aspect as if standing before me. Except that one could run a model train between her and the floor. As if in compliance, another express whistled and rumbled through the station across the street. Within this din, she swayed slightly, then began to move. The puddle steamed and crackled as she glided over it. Hovering inches off the floor, she made her way to the desk in the corner, leaned down and began opening drawers.

Methodically searching each, she half-shouted across the room.

“It was Da Nang, wasn’t it?”

I gazed at the magazine cover, turning it to see better.

“Yes. Early on.”

“I remember those months well. Very busy time for me.”

“I’m sure.”

“And in all that time, you were the only one to….”

She trailed off, having thought she’d found it.

“Make the deal?”

Disappointed, she opened another drawer. “Oh, let’s not call it a deal. ‘Arrangement’ sounds more civilized.”

“Alright,” I agreed.

“The religious mind is a bitch to untangle. Just can’t see things clearly.”

“And we all turn to God at that moment.”

“But not you.”

“No. I’m extremely clear on that.”

“Good for you. And especially good for me.”

“We’ll see.”

“Please. Fifty earthly years, gone in a blink, in exchange for an eternity? A solid triumph for me.”

“We’ll see.”

“Excuse me?”

“You haven’t found it.”

“But I will. I always do.”

“Yes, but I’m living on, hours past my due date.”

“True, but inconsequential.”

“To you, perhaps. But I’m enjoying every extra second.”

“Yes, well, that comes to an end soon. Incredibly soon in the grand scheme, wouldn’t you say?”

“Granted. But this 50 years. To have lived, loved, two wives, four children, three careers, traveled the planet, stood on mountaintops both within and without. This life you gave me. I’ve lived.”

“Yes, I know: you think it was worth it. We hear this all the time. Get back to me in a couple of weeks on that, won’t you?”

“Alright, but I have a question.”

“It better be good, because your observations are incredibly ordinary and, sorry to say, soon forgotten.”

“Oh, I’m aware of that.”

“Then by all means. Let us luxuriate in these gifted extra seconds. One question—only one—to be answered fully, truthfully.” She arched an eyebrow in my direction and drolly remarked, “What fun.’’

She closed the last drawer and drifted with a world-weary serenity to the couch. Whereupon she did luxuriate, settling in against the arm of the overstuffed sofa, her thin black leg-ends, spider-like, comfortably crossed. She reached for the scarf and wrapped it several times around her neck. Then, with elbows in the air, in that womanly way that stirs a man’s spirit, freed her tresses, which had grown noticeably longer, whiter in these few minutes. For the first time, I noticed the large green scarab ring on her right index finger.

She sighed with satisfaction, the large feline eyes again softly closing with pleasure.

“Mmm. Jasmine.”

Picking up the Life magazine, I stood, side-stepped around the trunk and handed it to her.

She raised her knees. The skirt hiking, she adjusted it for modesty’s sake and dug her twin stumps into the cushion, placing the magazine unopened on her thighs.

The cover of the magazine, dated April 1965, showed the interior of a military helicopter. Out the open door, hundreds of feet below, rows of crops. The door gunner, one gloved hand on his machine gun, the other blurring, flailing wildly in the air, his helmet-framed face an alarmed scream for help. On the floor, amidst spent cartridges, the pierced and bloodied body of the pilot, faceless behind the helmet and communications mask. A small caption to the lower left formatted in Mid- 20th-Century American Military haiku:

In a U.S. chopper

under heavy fire—

a door gunner screams,

a wounded pilot

fights for life

As befits this particular war there was no period. None in sight that early month, that early year.

She adjusted the scarab, smoothed the cover page with both hands.

“I love this picture. Always have.”

“Then I’m right. That is you?”

“That’s your question? And here I thought you were going to attempt to be profound or philosophical, as is usual. Well, that’s a relief. Yes, that’s me. How ever did you guess?”

“The size. Look how small the arm, the gloves, like a child’s. Even the boots.”

“How I hated adapting those boots. All leather lacing and nylon strappage. But you’re right. There I am, lying next to you, wounded, reverse spooning, my hand on your arm, keeping you alive. So we could talk.”

“Quite the chat as I remember.”

“Extraordinary situation. I don’t often intervene, actually appear in the field, as it were, at these times. More rare is that there is a photograph. Even rarer that it is the cover of, of all things, Life magazine.”

“Yes. Why not Time?”

“Or After Dark at the very least. But Life? Life its very self? How cliched! But we needed to talk, and you were so close to gone, out of reach, I had to make the essential, more intimate contact.”

“Then I guess I need to give you something, don’t I?”

She suddenly sang, “Hooray for Hollywood!” Legit broadway chest voice, straight out of the second row of the chorus.

“Forgive me. As we get closer to the moment, my enthusiasm, shall we say, lacks restraint.”

She actually licked her lips. “You were saying?”

“Your confidence is stunning.”

“And why shouldn’t it be?”

“Because of…” —I reached under the cushion of my chair, retrieving another copy of the same magazine, rushed it over to her—“…this.”

Taking it, she did not notice at first.

“And your point is?”

Then she noticed, and bolted straight up.

“I was browsing through a used book shop and found it.”

The magazine was identical. Except for one important detail: the other wounded crew member, the one lying behind me, with its hand gently on my arm, was not there.

She slowly raised her face to me, a deep sorrow in her eyes that seemed to turn gray in that very moment. She suddenly looked her age, tired.

“You broke out. That book shop. You weren’t supposed to…”

I stared hard at her: “Then I’m right: It never happened. The reason I’m not giving you what you want is because you weren’t there. The life I had, I didn’t really have it, did I?”

Sad, beaten, she whispered, “Oh, but you did. It just wasn’t real.”

From my desk, a single “clack” shot across the room. I had reached center.

The horror I had accepted in my mind was finally accepted in my soul.

She placed her hands upon the magazine cover, as if erasing the dramatic image forever.

“No matter. I’ve eight more, none as clever as you. Only have to deliver five of those eight. Then I get my feet back, and I’m dancing in the chorus again. Broadway without end, by the way.”

As I sat, she rose ceremoniously, as if borne by melancholy, until upright, donned her coat and hat, picked up a boot in each hand, then glided to a poised stillness. Closing her eyes, she spun slowly. The scarf, as if alive, lengthened, began wrapping her, one end clockwise, the other countering, overlapping with increasing speed, until she was encased, a cashmere cocoon, floating softly, lifting by heavy inches until it hovered over the trunk table, towering above me.

A spark leaped from the candle. The flames began at the bottom, at the tight taper of her leg-sticks, licking upward, then—in seconds—engulfing the mummy like shape, which—legs to head—vanished without heat, smoke, smell or ash.

I reached into my pocket. The Purple Heart was gone.

A rushing wind blew through the room, the smell of human waste pulled into the cabin from the fields below. The roar of the copter engine, the rush of the blades filled my helmet. The room went sideways as I collapsed onto the deck of the careening Choctaw helicopter. The crew chief screamed at the co-pilot. The machine gun rattled and poured death on an empty field. I bounced off the metal floor, more corpse-like with every round.

Her face–young, astonishingly beautiful, framed within a corona of undulating raven-black hair–appeared before my inner gaze. The eyes glowed jade with points of gold.

Her lips, full and lizard green, parted.

And she began to speak.

Again.

#